Many of us who have worked in the field of Jewish education for a long time believed that we “had seen it all.” Aside from all else that the coronavirus pandemic has shown us, we have learned that we haven’t seen it all and probably never will. It certainly has brought the professional hubris down a peg or two.

So what was new and inspiring? What were some of the most creative approaches and innovative programs that surfaced in day schools? I’m enthusiastic to celebrate schools’ successes, visionaries, and takeaways that have the potential to change the field in positive ways moving forward. I’m grateful to the many Jewish day school stakeholders who shared good news and optimism through individual conversations and group convenings such as JEIC’s virtual 2020 Innovators Retreat.

Here’s the first piece of good news: Collaboration is growing and it matters.

Collaboration is on the rise, both among teachers in the same school and between different schools in the same or diverse geographical regions. As I remarked, “b’zman hitbodedut, ayn tacharut: At a time of isolation, there is no competition.” [It sounds a bit more poetic in Hebrew because it rhymes.] This increased collaboration bodes well for now and the future; working together is a Jewish imperative, as the Talmud in Tractate Bava Batra 22a states, “kinat sofrim tarbeh chochmah: A healthy competition increases wisdom.” In that spirit, we appreciate the Jewish Community Relief Impact Fund for promoting collaborative grant opportunities among Jewish day schools.

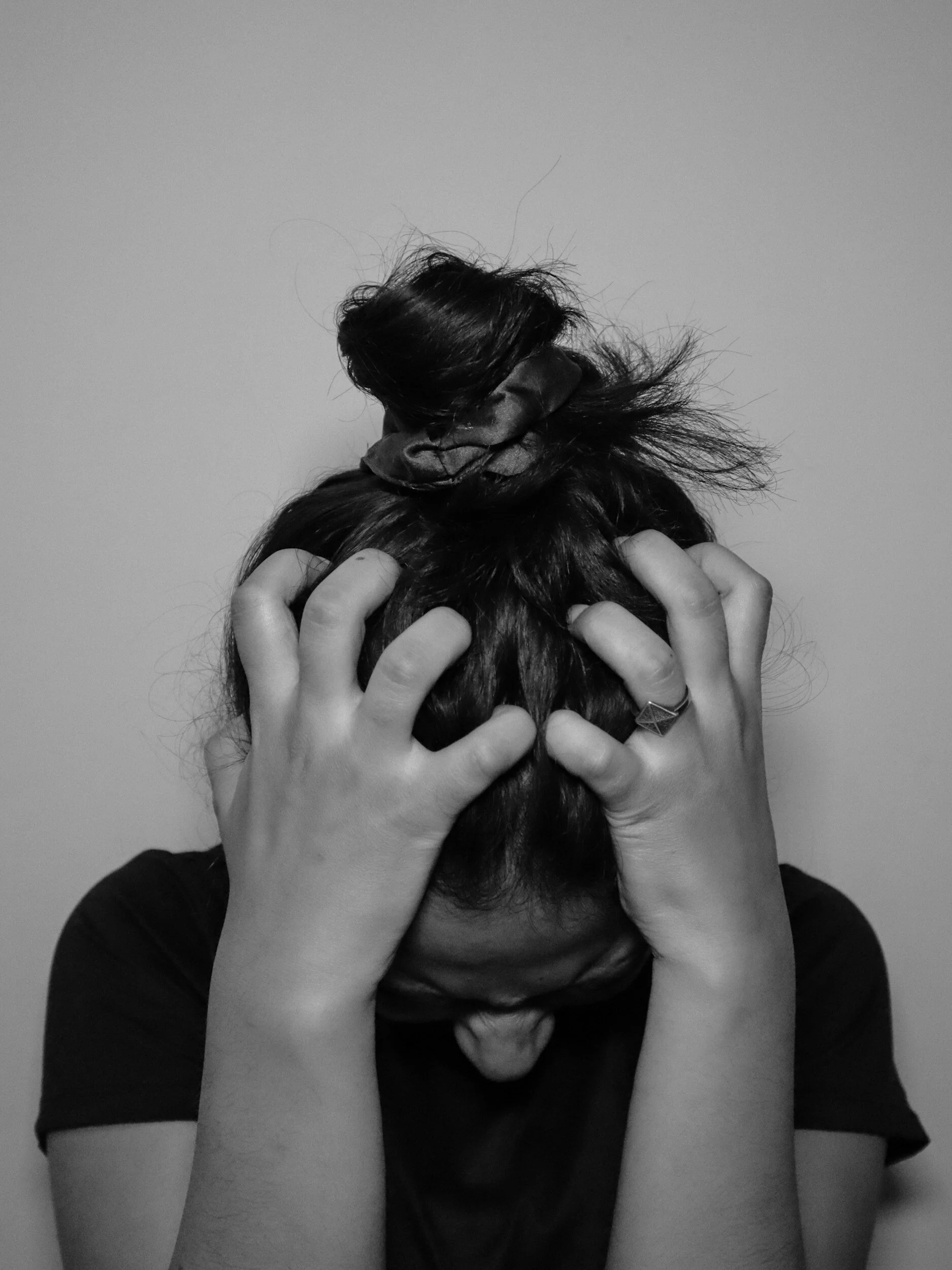

Here’s the second piece of good news: Day school professionals remain resilient and dedicated to their work.

Despite administrators and teachers being exhausted and running on fumes, they have demonstrated their abiding commitment to their calling of imbuing our students with Jewish wisdom and values. Our educators and leaders have powered through and continue to power through the greatest crisis in our lifetimes. To quote a head of school, “This is not just a financial crisis, but this is also a values crisis. We need our schools to ensure that we as a people have a future.” Added another educator, “Changes are causing us to reemphasize what is important.” Like the aspect of collaboration mentioned above, rethinking our values including the importance of teachers―also mentioned in Tractate Bava Batra―is one outcome that should outlive the current crisis.

Here’s a third piece of good news: Creativity and innovation abound.

The abundance of creativity that has appeared in classes, co-curricular sessions, and special events is remarkable. Below are a few examples without attribution to school, since I am confident similar things are happening in various schools around the country.

Daily school announcements on social media enfranchise every staff member in the virtual school effort. Each day, morning announcements were made in different and interesting ways by a different staff member―not only teachers and administrators―but the security guard, the bus driver, the office staff, the housekeeping crew, and various other adults involved in the school. This allowed students to see trusted adults from school who were not in their Zoom classes.

Teachers are varying instructional strategies in virtual classrooms. I observed a teacher in a Beit Midrash course presenting a concept to the whole group, followed by student chevruta/partner work in virtual breakout rooms culminating with each student individually submitting their developed understanding of the text. In a 45-minute virtual class, the teacher supported a short frontal presentation, small group work, and individual culminating essays serving as an exit card and formative assessment. The lesson was broken down into manageable chunks and the students played an active role, leaving little room for zoning out while staring at the small boxes showing their teacher and classmates.

Thoughtful planning can maintain treasured rituals and relationships that engage students in learning and community. I was fortunate to join a Thursday morning school tefillah, during which all students were required to have their cameras turned on so that “they could be part of the tzibbur [community] experience,” and in which the words of the prayers/Torah reading were shared on screen. The tefillah included student shlichei tzibbur [prayer leaders] and baalei kriah [Torah readers], as well as a D’var Torah given by the principal with the explicit message of “You count!” As I watched the faces of the children and the many faculty members present, I could see how the forethought and preparation of this tefillah session were quenching students’ and teachers’ thirst for connecting as a community.

Graduations are retaining traditions while creating personal connections. I had the honor of witnessing a high school graduation, where each graduate took a favorite personal item and “passed it” to the graduate in the next Zoom window in lieu of the traditional processional. Many classic features of graduation―such as faculty remarks or student awards―were retained (albeit pre-recorded), which gave the ceremony a sense of familiarity. The administrators actually visited each student’s home to present them their diploma and received awards―with the student wearing full graduation regalia. These presentations were pre-recorded and presented with a voice-over by an administrator, laying out each student’s achievements and strengths.

The similarities that I see among all of the good news items are intentionality, thought, and reflection on how we can best keep our students connected emotionally, spiritually, and academically. To me, this intentionality bodes well for the future of Jewish day school education. So thank you to all of the stakeholders in Jewish day school education who have not only kept school going during the current situation, but have elevated their practice in numerous ways.